Return To Basics: Python List, Append, Extend, Copy, Deepcopy, and Assignment

I often see confusion regarding the various tools that Python gives us to copy data from or to lists. Understanding how they behave under the hood will help you avoid weird bugs and write more efficient code.

When you are managing global configurations or parsing massive log streams, memory efficiency is often the difference between a lean pipeline and a crashed node. In DevOps environments, where automation and data flow are constant, even small misunderstandings about how Python handles copying and mutation can lead to subtle, hard-to-trace bugs.

At Digitalis, we regularly see performance bottlenecks and unexpected behaviour caused by assumptions about how lists are copied or shared across threads and services. Understanding these under-the-hood mechanics is not just a Python curiosity - it is a practical skill that leads to more predictable automation, safer tooling, and more resilient infrastructure.

First, a little bit of basics

What is a Python List?

A Python list is a dynamic, ordered, mutable collection of references to objects. You can think of it like an array of pointers. It doesn’t store the values directly; it stores references (memory addresses) to the objects.

1my_list = [1, "hello", [3, 4]]Under the Hood

Python lists are implemented in C (in CPython), and they work like a dynamic array (like std::vector in C++ or ArrayList in Java).

Python internally keeps a contiguous block of memory to store references to the objects. The list tracks the size of the list, that is, the actual number of elements in the array, and the allocated actual space reserved, which can be larger than the size.

Growth Strategy

When you do append() or extend(), see description below, Python may allocate extra space in advance to avoid copying the list every time you grow it.

To see it practically:

1import sys

2l = []

3for i in range(10):

4 l.append(i)

5 print(f"len={len(l)}, size={sys.getsizeof(l)}")

Output:

1len=1, size=88

2len=2, size=88

3len=3, size=88

4len=4, size=88

5len=5, size=120

6len=6, size=120

7len=7, size=120

8len=8, size=120

9len=9, size=184

10len=10, size=184

The list doesn’t grow in memory size with every single append, it’s amortized.

When Should You Use a List?

- When order matters.

- When you need dynamic resizing.

- When your data is heterogeneous (mixed types).

- When you are not doing heavy numerical work (for that, use numpy arrays).

Append, Extend, Copy, Deepcopy, and Assignment

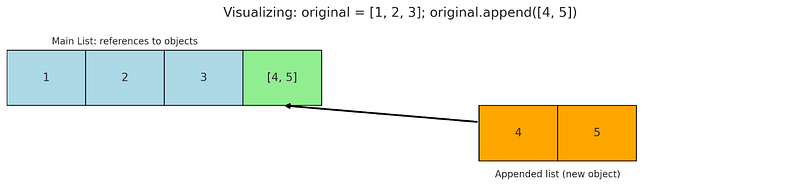

Let’s explain: append()

append() adds one element at the end of the list, even if that element is another list.

Simple example:

1original = [1, 2, 3]

2original.append([4, 5])

3print(original) # [1, 2, 3, [4, 5]]

What’s going on under the hood:

Python internally resizes the list and adds a reference to the new item at the end.

When you can use it:

When you want to add one thing (could be a list, object, number, etc.) as a single item at the end.

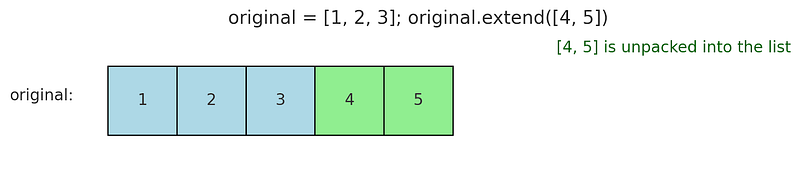

Let’s explain: extend()

extend() takes an iterable and unpacks it into the list.

Simple example:

1original = [1, 2, 3]

2original.extend([4, 5])

3print(original) # [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

What’s going on under the hood:

Python loops over the iterable and appends each element individually. It is more efficient than doing a loop yourself in Python.

When you can use it:

When you want to merge another list (or tuple, etc.) into your list, flattened.

Let’s explain: copy() (shallow copy)

copy() makes a new list object, but its contents are still references to the original elements.

So if the elements are mutable objects (like inner lists), both lists still share them.

Simple Example:

1original = [[1, 2], [3, 4]]

2shallow = original.copy()

3shallow[0][0] = 100

4

5print(original) # [[100, 2], [3, 4]]

6print(shallow) # [[100, 2], [3, 4]]If you use .copy() on a list that contains immutable types (e.g. int, str, float, bool, tuple), the references are copied, but it’s usually not a problem because those objects can’t be modified anyway.

To see that with code:

1original = [1, "hello", 3.14]

2copied = original.copy()

3

4print(original is copied) # False -> they are different lists

5print(original[0] is copied[0]) # True -> they point to the same int objectTechnically, the immutable types are shared references. But because the values can’t be mutated, you won’t notice it.

Let’s illustrate this with code:

1a = [42, "ciao"]

2b = a.copy()

3b[0] = 100 # This just replaces the whole reference

4print(a) # [42, 'ciao'] — original unchangedWe are not mutating 42; we just replaced that element in the copied list with a new number.

What’s going on under the hood:

Python allocates a new list but it doesn’t clone the objects inside. It just copies references to them. This is faster and less memory intensive than a deepcopy (see the deepcopy explanation below).

When you can use it:

When you want a new list, but you don’t mind if inner mutable elements are shared.

Let’s explain: deepcopy() (from copy module)

deepcopy() creates a completely independent clone of the original object, including all nested structures.

Even deeply nested items are copied recursively.

Simple example:

1import copy

2

3original = [[1, 2], [3, 4]]

4deep = copy.deepcopy(original)

5deep[0][0] = 100

6

7print(original) # [[1, 2], [3, 4]]

8print(deep) # [[100, 2], [3, 4]]What’s going on under the Hood:

It traverses the object tree and rebuilds everything from scratch. It also handles circular references smartly.

When you can use it:

When you want to safely mutate a nested structure without affecting the original.

Let’s explain: Assignment (Copy only the pointers)

Assigning a new variable to a list will not copy the content but only create a new reference to the same list.

Simple Example:

1original = [1, 2, 3]

2copy_pointer = original

3copy_pointer.append(4)

4print(original) # [1, 2, 3, 4]The assignment copy_pointer = original does not make a new list; in fact, both original and copy_pointer point to the same object in memory. If you change one, the other changes too. This is called a shallow reference.

What’s going on under the Hood:

Python just creates a new reference to the same list object in memory. No memory is duplicated.

When you can use it:

You want a second name (alias) for the same list and you intend to modify the original.

Conclusion

Knowing what is going on under the hood will help you write better code. I hope that with this article, I gave you a glimpse into the beauty of Python.

Subtle behaviours like list mutation rarely fail loudly. They surface later, under load, across services, or inside shared state, when assumptions meet reality.

Taking the time to understand how Python actually handles copying isn’t about memorising theory. It’s about building systems that behave exactly as intended, even when complexity increases.

The more intentional you are with how data is duplicated and shared, the more predictable your automation becomes. And in infrastructure work, predictability isn’t a luxury; it’s the foundation.

Contact our team for a free consultation to discuss how we can tailor our approach to your specific needs and challenges.

.png)