Back to basics: routing

.png)

Introduction

For the last decade, “multi-cloud” has mostly meant optionality: keeping a foot in two hyperscalers to hedge outages, negotiate discounts, or satisfy an audit checkbox. In 2026, it increasingly means something sharper: reducing strategic dependency on US-controlled platforms, and putting European jurisdictions, operators, and providers back in the critical path for sensitive workloads and essential services.

.webp)

The challenge is that dependency is real and measurable: roughly two-thirds of cloud services in Europe are still delivered by US firms, and a large portion of organisations say they couldn’t operate if their primary cloud provider failed. That combination of concentration plus lock-in, turns what used to be “vendor risk” into a board-level resilience and sovereignty problem, spanning everything from outage blast radius and pricing power to extraterritorial legal exposure (for example, the US CLOUD Act).

Here is a great article by Simon Hansford on the subject I recommend you read.

When I talk to customers about their cloud provider choices, the response is almost always the same: hyperscalers are easy to use and provide everything they need. And they're not wrong. AWS, Azure, and GCP have built comprehensive ecosystems of managed services that genuinely do simplify many aspects of infrastructure management.

But I've started to wonder whether this convenience narrative has created a blind spot. Somewhere along the way, we've conflated "managed by a hyperscaler" with "complex to do yourself," when in reality, many of the capabilities that feel proprietary or difficult are actually straightforward to implement.

Routing between cloud providers is a perfect example. It sounds exotic, perhaps even risky. But the underlying primitives like BGP, VPN tunnels, private interconnects, DNS steering, and API-driven traffic management are well-understood, battle-tested technologies. The tooling has matured significantly: Terraform providers for European clouds are solid, Kubernetes CNI plugins handle cross-cloud networking, and open-source service meshes can federate identity and traffic across boundaries you control.

Years ago, when I started working in IT, long before "cloud" meant anything beyond weather, my day-to-day was racking servers and routers, then spending hours in CLI sessions getting them to talk to each other. I absolutely loved working on Cisco and Juniper routers; so much so that I ended up getting my CCNP and JNCIA certifications. Those were the days: late nights in cold data centres, BGP peering sessions that finally converged at 2am, and the satisfaction of building something you could physically touch and logically understand from end to end.

I want to pull back the curtain and show you that the "magic" happening behind the scenes at hyperscalers is anything but. It's just good engineering, wrapped in a nice API and a generous marketing budget.

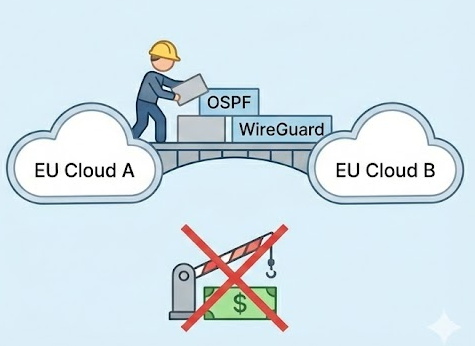

To prove it, I'm going to walk you through something many people consider genuinely difficult: routing traffic between two cloud providers. And because I'm feeling nostalgic for those late-night data centre sessions, I'm going to intentionally overcomplicate parts of it by adding OSPF to include the internal network routing instead of the most straightforward static routes just to demonstrate that even the most elaborate setups are actually quite manageable once you understand the fundamentals.

If I can make that look straightforward, imagine how simple the everyday stuff really is.

A more modern approach, specially for small networks, would be to use a fully-mesh network instead. You can read more about it on this previous blog post.

The Set-Up

I have two data centers. In this case, they're both European cloud providers, but this approach will work for any setup, including on-premises infrastructure or a mix of hyperscaler and sovereign cloud.

.webp)

The router on DC A has a public IP and connects to two internal networks: 10.10.0.0/16 and 10.20.0.0/16. The router on DC B also has a public IP and connects to two internal networks: 172.16.1.0/24 and 172.16.5.0/24.

The goal is for fully internconnect the nodes on both sides of the network so that a server for example with the IP address “172.16.1.99” can connect to another in “10.10.1.55”.

The Hook

The first task is to provision a Linux server on each DC. I’m using Debian but you can follow this guide with minor changes on any other flavour. Because we’re going to be performing routing over the internet, we need to secure the connection. You can use IPSec like OpenVPN or much simpler, Wireguard.

1. Install wireguard on both nodes and enable IP forward

1sudo apt update

2sudo apt install wireguard

3sudo sysctl -w net.ipv4.ip_forward=12. Create the public and private keys

sudo umask 077

wg genkey | sudo tee /etc/wireguard/wg.key

sudo cat /etc/wireguard/wg.key | wg pubkey | sudo tee /etc/wireguard/wg.pub3. Configure it

I have chosen here the network 10.10.10.0/24 for my Wireguard network.

On Server A

1[Interface]

2Address = 10.10.10.1/24

3ListenPort = 51820

4PrivateKey = <paste contents of /etc/wireguard/wg.key>

5

6[Peer]

7PublicKey = <paste contents of Server B /etc/wireguard/wg.pub>

8# AllowedIPs = WireGuard Subnet, OSPF Multicast IP

9AllowedIPs = 10.10.10.0/24, 224.0.0.5/32

On Server B

1[Interface]

2Address = 10.10.10.2/24

3PrivateKey = <paste contents of /etc/wireguard/wg.key>

4

5[Peer]

6PublicKey = <paste contents of Server A /etc/wireguard/wg.pub>

7Endpoint = <ServerA_public_ip_or_dns>:51820

8# AllowedIPs = WireGuard Subnet, OSPF Multicast IP

9AllowedIPs = 10.10.10.0/24, 224.0.0.5/32

10PersistentKeepalive = 25

And just start it up:

1sudo systemctl enable wg-quick@wg0.service

2sudo systemctl start wg-quick@wg0.serviceThe Tale

We have now two routers communicating with each other. And essentially, four networks connected. The only thing that is stopping a server from A to talk to another in B is the missing routes. The easy part would to just add the static routes like so:

1# in router A

2route add -net 172.16.1.0/24 via 10.10.10.2

3route add -net 172.16.5.0/24 via 10.10.10.2

4# in router B

5route add -net 10.10.0.0/16 via 10.10.10.1

6route add -net 10.20.0.0/16 via 10.10.10.2

But, as I promised, who needs easy when we can complicate things!

The Sting

OSPF (Open Shortest Path First) is a link-state routing protocol that allows routers within the same network to automatically discover each other, share information about the networks they're connected to, and calculate the best paths to reach every destination.

In this setup, we're using OSPF to dynamically advertise the internal networks (10.10.0.0/16, 10.20.0.0/16, 172.16.1.0/24, and 172.16.5.0/24) between DC A and DC B without having to manually configure static routes every time the topology changes. Once the routers establish neighbor relationships and exchange their link-state information, they'll automatically know how to reach each other's internal subnets and will adapt instantly if a link goes down or a new network is added.

The FFRouting Project is a relatively new project based on Quagga which I discovered in the 2000s when I worked for UK based ISP. frr provides implementations for most of the internet routing protocols like OSPF. It’s a default package in all modern linux distros so it’s very easy to install it to get up and running.

- Install

1apt -y install frr- Enable OSPF

OSPF is not enabled by default. You’ll need to edit the /etc/frr/daemons and set ospfd=yes. Then, restart the service for the changes to take effect with systemctl restart ffr

- Configure

The configuration is the same on both routers. Just be mindful that the network interfaces may have different names as this is dependant on the OS, hardware and underlying virtualisation platform.

Launch the configuration interface with the command vtysh and type configure to enter into configuration mode.

1interface eth1

2 ip ospf area 0

3 ip ospf passive

4exit

5!

6interface eth2

7 ip ospf passive

8exit

9!

10interface wg0

11 ip ospf area 0

12!

13end

14wr What we’re doing here is enabling OSPF for the point to point network (wireguard, interface wg0). Then, we do the same thing for each of the network interfaces where our internal networks are connected with an additional parameter, ip ospf passive which prevents us from leaking OSPF packages to the internet.

Confirm it’s all working:

1dca-router# show ip ospf route

2============ OSPF network routing table ============

3N 10.10.0.0/16 [10] area: 0.0.0.0

4 directly attached to eth1

5N 10.20.0.0/16 [10] area: 0.0.0.0

6 directly attached to eth2

7N 172.16.1.0/24 [20] area: 0.0.0.0

8 via 203.0.113.20, wg0

9N 172.16.5.0/24 [20] area: 0.0.0.0

10 via 203.0.113.20, wg0

11

12============ OSPF router routing table =============

13R 10.10.10.2 [10] area: 0.0.0.0, ASBR

14 via 203.0.113.20, wg0

15

16============ OSPF external routing table ===========How to read the routing table: the “cost” of a directly connected route is 10. Remote networks over OSPF have a cost of 20. As you can see, we have two local and two remote.

That’s it! Disappointed it’s not more difficult?

Closing Thoughts

If you've made it this far and followed along, you've just built something that many organisations assume requires a hyperscaler's managed networking service: dynamic, resilient routing between two cloud providers with automatic failover and path optimization. No proprietary SDN controller, no vendor-specific APIs, no multi-thousand-pound monthly bill for a "transit gateway" service. Just open protocols, a bit of configuration, and the kind of fundamental networking knowledge that's been around for decades.

This is the point I wanted to drive home: managing your own infrastructure isn't the dark art that hyperscaler marketing wants you to believe it is. Yes, AWS and Azure have made certain workflows more convenient, but convenience isn't the same as necessity. The primitives - routing protocols, VPN tunnels, DNS, load balancing - are mature, well-documented, and increasingly accessible through European cloud providers who offer the compute, storage, and network building blocks without the jurisdictional baggage or lock-in penalties.

For organisations serious about cloud sovereignty, this approach gives you something genuinely valuable: multi-cloud resilience on your terms, within European jurisdiction. You're not dependent on a single US-controlled platform for routing decisions, identity management, or encryption key custody. You can migrate workloads incrementally, test failover scenarios without vendor permission, and negotiate from a position of strength because your infrastructure isn't welded to someone else's API.

The hyperscalers aren't going anywhere, and for certain workloads they'll remain the pragmatic choice. But for the workloads that matter most (sensitive data, core business logic, anything subject to regulatory scrutiny, data sovereignty) taking back control is not only possible, it's increasingly straightforward. You already have the skills. The European providers have the infrastructure. All that's left is deciding whether strategic independence is worth the modest engineering effort to set it up.

If this guide has shown you anything, I hope it's that the barrier isn't technical, it's psychological. And that barrier is lower than you think.

I for one welcome our new robot overlords

.png)